In the first part of this chapter, I projected that 133 of the 164 districts would be competitive, and that 227 of the 695 seats would be competitive. I also projected that Democrats would safely win 221 seats and Republicans would safely win 192 seats, while a competitor from the left (Progressives) would win 36 seats and compete in 79 more, and a competitor from the right (Libertarians) would win 19 seats and compete in 89 more. For projecting the outcome of the current maps, I used the projections from the September 2023 Cooks Report, which rates the competitiveness of each Congressional race.

These estimates for the new maps are for the first election in such a system and are likely an undercount of the number of competitive districts and competitive seats that would emerge as the multiparty system develops and voters and political parties adapt to the new voting rules. I anticipate that more parties would quickly become electorally viable and that within two decades every single Congressional district would be competitive.

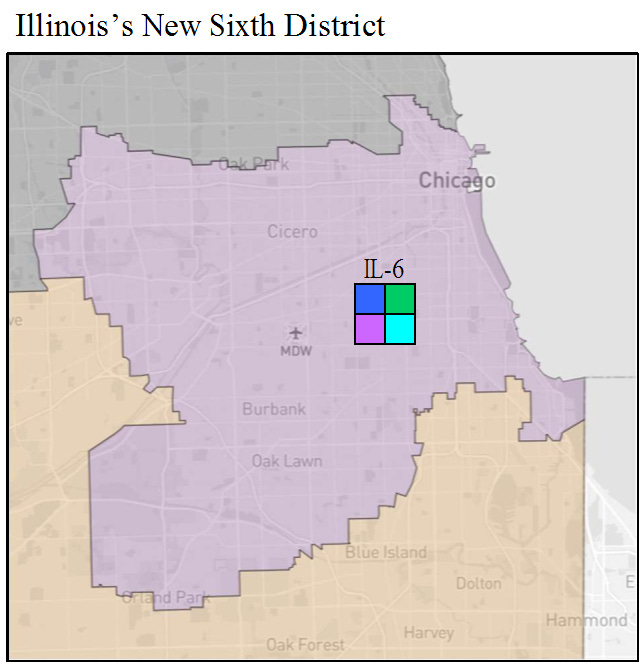

Legend for all maps; the color of each square represents the party I expect to win each seat.

For this analysis, I first looked at each district’s expected share of Democratic and Republican voters. Dave’s Redistricting helpfully aggregates statewide election results from 2016 – 2020 and uses that data to provide an estimated number of Democratic and Republican voters in each precinct. For example, the new California First District, a geographically sprawling five-member district next to Oregon and Nevada, is expected to have 50.4% Dems and 47.4% Reps.

Second, I assume that roughly 40% of each party’s voters would be willing to vote for an alternative party. This assumption is based off Gallup’s 2022 research showing that 56% of Americans believe a third-party is needed, and Pew Research Center’s 2022 research showing that nearly 40% of Americans wish there were more political parties to choose from.

The 40% assumption is a more of a rule of thumb than a strict demarcation. In politics, you must expect the unexpected; you must keep your mind open to low-probability events. All of the data analyzed here is from 2016 through 2020, yet in some ways it already feels out of date because politics changes so quickly. Further, every state and region has idiosyncratic politics. In districts with similar partisan projections, alternative parties may be more popular in one part of the country than another part of the country. People that vote for Democrats in New York could have a very different collective preference for a Progressive Party than people that vote for Democrats in Texas; people that vote for Republicans in Washington could have a very different collective preference for a Libertarian Party than people that for Republicans in Florida.

State and regional idiosyncrasies aside, in general, the more members in a district means there is a lower electoral threshold, and the more likely an alternative party could be competitive to win more than 1 seat. For example, in a five-member district, I would expect alternative parties to be competitive for one seat when a major party reaches about 40% of the vote and to win one seat when a major party reaches about 42% of the vote. In a four-member district, alternative parties could be competitive when the major party reaches about 45% of the vote and could win one seat when the major party reaches about 50% of the vote. In this way, alternative parties are viable not just in the most liberal cities or most conservative exurbs, but in more evenly divided districts across every part of the country.

Even if someone wanted to gerrymander these districts, there are too many competitive thresholds to consider. Imagine trying to gerrymander a 4-member district to ensure one party will win 3 seats. In a two-party system, you could draw a district so that your party was projected to win 63% of the vote, a comfortable margin above the 60% electoral threshold to win 3 seats in a 4-member district. In doing so, you would guarantee one seat to the opposing major party. But you would also be practically ensuring an alternative party or independent candidate will compete for one of your seats! An alternative party would need to win just one third of your party’s voters to win 20% of the vote. The electoral outcome would be 2 seats for your party, 1 seat for the opposition, and 1 seat for an alternative party. To ensure 3 seats, you would have to draw the district so that more than 80% of voters are projected to vote for your party. This is practically impossible; there are very few parts of the country in which it is possible to draw such a large district with such a large partisan majority. Gerrymandering only works in our current system because we use single-member districts, which are far easier to gerrymander than multimember districts.

The table is the data and my analysis explaining the reasoning for the projections of three districts, using the 40% rule of thumb as a baseline. Chapter 8 explains my reasoning for all 164 districts across all 53 states.

I project CA-1 would elect 1 Democrat and 1 Republican, with a third seat competitive between the two parties. Additionally, one seat would be competitive between the Democrats and a Progressive Party, and one seat would be competitive between the Republicans and a Libertarian Party. With just 17% of the vote necessary to win one seat, each of the major parties would have to contend with a challenge. In the existing two-party system, Democrats are projected to win 50.4% of the vote in CA-1. Is it plausible that 40% of Democratic voters would support a Progressive candidate? Similarly, Republicans are projected to win 47.4% of the vote. Is it plausible that 40% of Republican voters would support a Libertarian Party, or some other conservative leaning political party? Absolutely! Both alternative parties could plausibly win 1 seat. Depending on how the ranked choice voting shook out, CA-1 could end up electing a delegation of with representatives from four different parties.

I projected “safe” Progressive and Libertarian seats in districts with large Democratic or Republican majorities. For example, because Democratic voters make up 75.4% of Illinois’ four-member Sixth District (Chicago), it is highly likely that a Progressive or independent left-wing candidate would win 20% of the vote. Similarly, because Republican voters make up 73.3% of Texas’ five-member Second District (Lubbock, North Texas), it is highly likely that a Libertarian or independent right-wing candidate would win 17% of the vote, and plausible for a Libertarian Party to challenge the Republicans for 34% of the vote and a second seat.

Again, this analysis is likely an undercount because it is based off election data from our current single-member district, two-party system! This proposal’s method of lowering the electoral threshold and reversing gerrymandering would certainly have unknown consequences. I use Progressive and Libertarian parties in this analysis because these ideas already exist in our politics today. But new ideas, and new coalitions, would emerge in a system like this, designed to foster competition among parties. The tired, old, sclerotic Democratic and Republican parties might be eclipsed by successor parties, just as the Whigs faded in the years leading up to the Civil War.

Ch. 7.c: A Note on Data

All population data used in creating and analyzing these maps is from Dave’s Redistricting, based on the 2020 US Census. These population figures are slightly different compared to the 2020 Census figures used for apportionment in the Chapter 5, on average 0.11% lower.

The difference is so slight that it does not impact my purpose here, which is to show what a cube root Congress elected by ranked choice voting in multimember districts might look like. These maps are not intended to be perfect; if we implemented multimember districts, new maps would be drawn and approved by the people of each state.