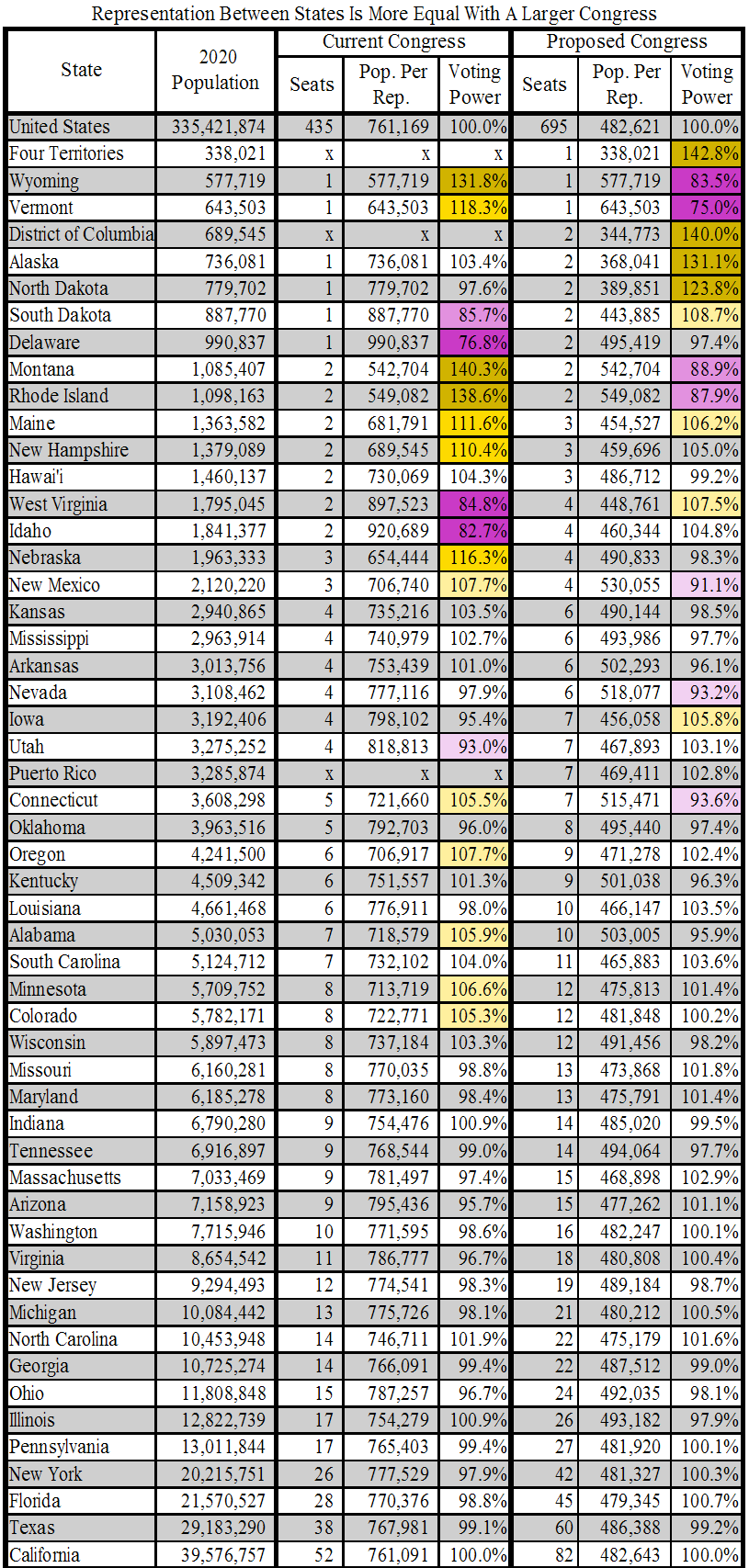

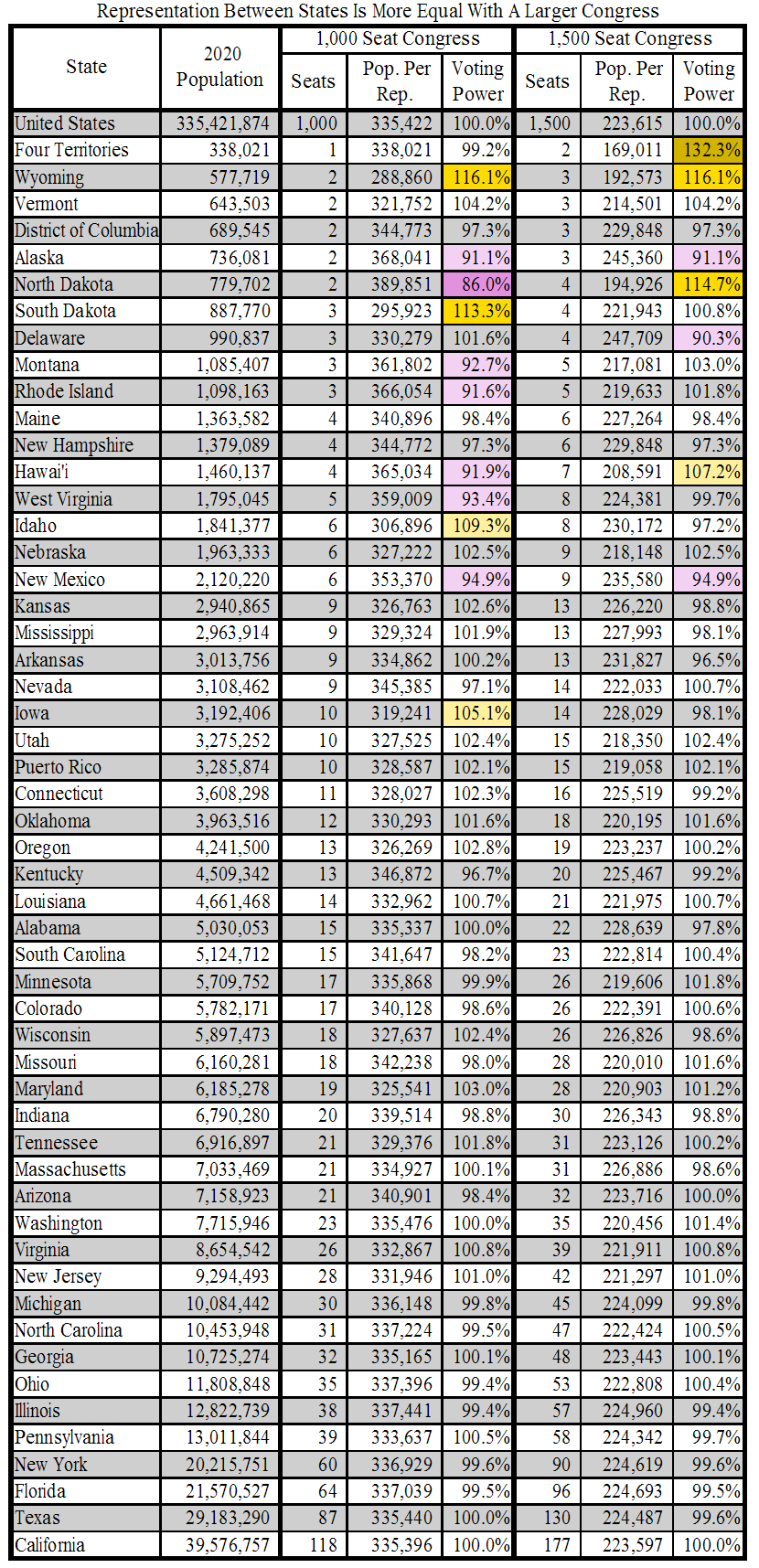

Note: All tables in this section assume there are 53 States as described in the previous section. I use the Priority Value method to assign the appropriate number of seats to each state depending on the size of Congress.

In an ideal democracy, every person would have exactly equal representation in Congress. That is impossible if we are to remain divided into states, which then are apportioned representation based off state populations. Instead, our goal should be to (a) minimize the inequality ratio between the most over- and under-represented states, and (b) maximize the population within 5 percent of average national representation so that the inequality ratio between most citizens is no more than 1.1.

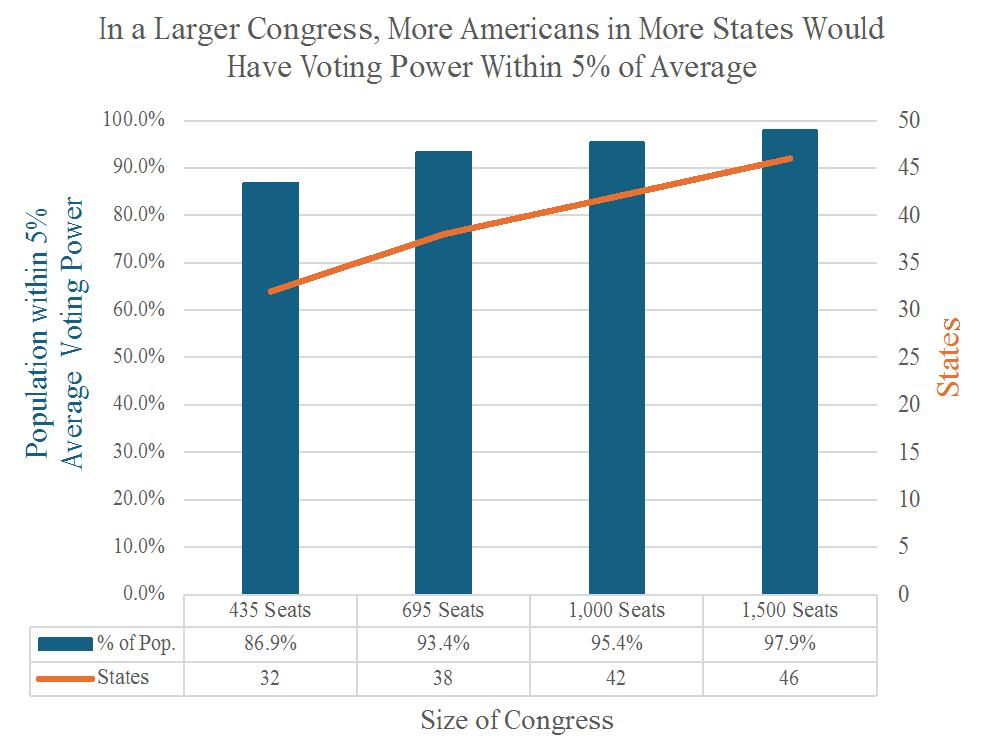

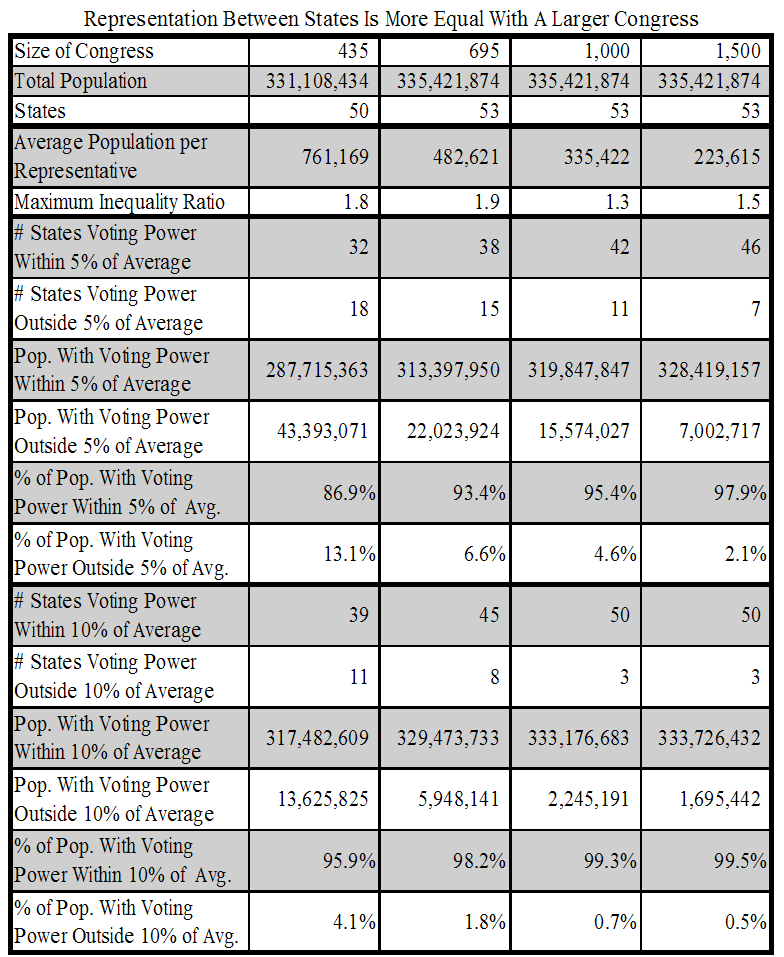

As shown in Figure 5.1, the larger the Congress, the more equal representation becomes across the states. In our current Congress, based off the 2020 Census, 288 million Americans (87 percent of the population) across 32 states have voting power within 5 percent of the national average. Only 4 percent of Americans, 13.6 million people across 11 states, have voting power greater or less than 10 percent of the national average. All 11 outlier states are among the smallest states; the largest outlying state is Nebraska, the 37th most populous state.

A larger Congress reduces the number of outlying states and increases the number of Americans with voting power within 5 or 10 percent of the national average. In a 1,500 member Congress, 98 percent of Americans living in 46 states would have voting power within 5 percent of the national average, and 99.5 percent of Americans living in 50 states would have voting power within 10 percent of the national average (the three outlier states would be the Four Territories, Wyoming, and North Dakota).

Interestingly, the Maximum Inequality Ratio for a 1,500 member Congress is higher than for a 1,000 member Congress. This is due to the difficulty of apportioning the smallest state, the Four Territories. By the Priority Value method, the Four Territories would be assigned the 1,406th seat in Congress. In a Congress around the size of when the smallest state would receive its second seat, the Maximum Inequality Ratio will be high because that smallest state would either be highly under- or overrepresented. Additionally, the population of the Four Territories is almost exactly 1 one thousandth of the total population of the United States, meaning that the Four Territories are almost perfectly represented by 1 representative in a 1,000 member Congress. In effect, states that are apportioned 1 or 2 states remain in a lottery. Once Congress is large enough that every state receives 2 or 3 seats, the representation variability decreases.

But we cannot increase the size of Congress indefinitely. By definition, representative democracy must have representatives; all 335 million Americans should not be asked to vote on every proposal.

At what point would Congress be too big?

The highest proposed size of Congress comes from Thirty-Thousand.org, which advocates for increasing the size of the House to between 6,623 and 11,036 Representatives. With that massive a House, there would be one Representative for every 30,000 to 50,000 Americans. Representation across the states would be very close to equal, as even the smallest state would have at least 7 or 8 representatives. (That is an educated guess. I did not model a 10,000 seat Congress.) That would be similar to the population per representative of the United States from 1790 – 1830. Thirty-Thousand bases much of their argument on a proposed but never ratified amendment during the passage of the Bill of Rights which would have limited the number of people per Representative to 50,000. But I find an argument based on deification of the Founders unpersuasive: the Founders never could have imagined a united country of more than 330,000,000 Americans. And if they had, would they really have wanted Congress to have more than 6,000 members? A Congress with 6,000 members would have been the 10th largest city in 1790 America!

Reasonable people can disagree about the optimal size of Congress. In Parliamentary America, Stearns proposes doubling the size of Congress to 870. Half of the Congress would be elected in the same way it is now, while the other half would be elected in a party list vote similar to those in New Zealand and Germany (more on this in Chapter 6). Stearns chooses this number to make increasing the size of Congress more politically palatable to incumbents in the existing 435 single member districts.

Yet choosing any specific number of representatives feels arbitrary because, at the end of the day, it is. We make the rules up as we go. Lacking a human authority to whom we might appeal, let us appeal to math: Congress should be the size of the cube root of America’s total population. For 2020, that would mean a Congress of 695 members representing 335 million Americans, for a national average of 482,397 people per representative. (The cube root of 335 million is 695 because 695 times 695 times 695, or 695^3, is 335.7 million.)

Why the cube root? First described by political scientist Rein Taagepera in the 1970s, the cube root function is the strongest empirical relationship between the size of a population and the size of its legislature. Or, as Professor Emeritus Matthew Shugart of UC Davis put it, “A nation’s assembly tends to be about the cube root of its population.”

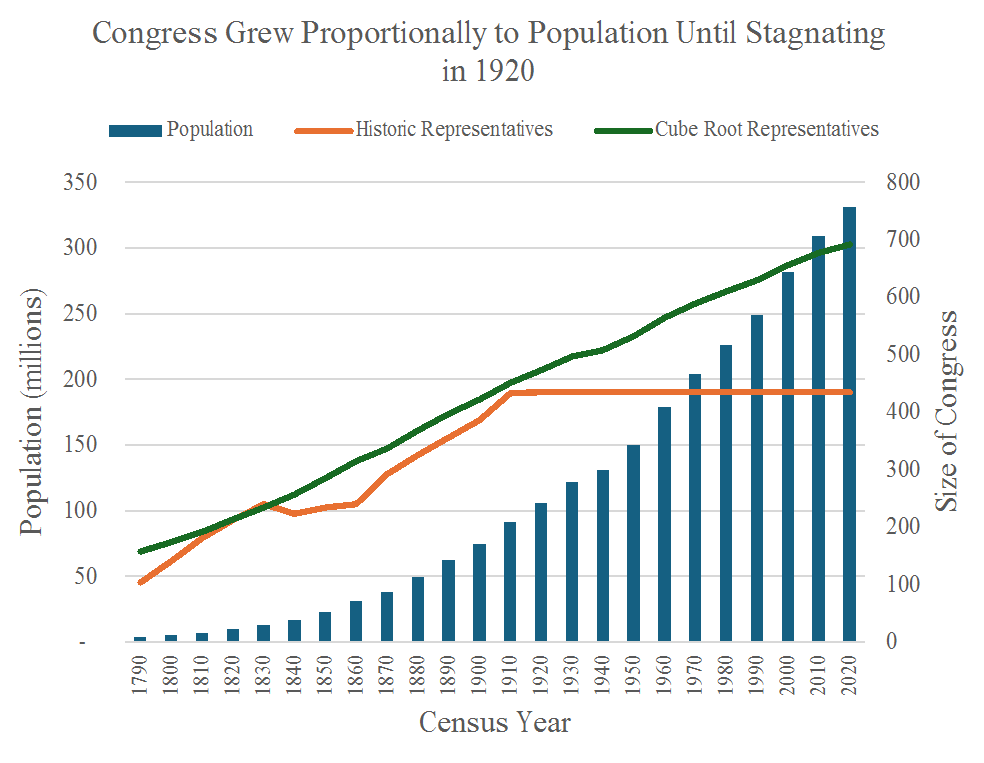

This holds true for the United States, too. In the below figure, the orange line shows the historic size of Congress. From 1790 until 1910, under its varying apportionment methods, Congress was close to the size of the cube root of the total population, the green line. (This includes enslaved people, who did not have representation). It was only when Congress stopped increasing its size despite a booming population that Congress deviated substantially from the cube root function.

Increasing Congress to 695 members would restore its historic relationship with the total population of the country.

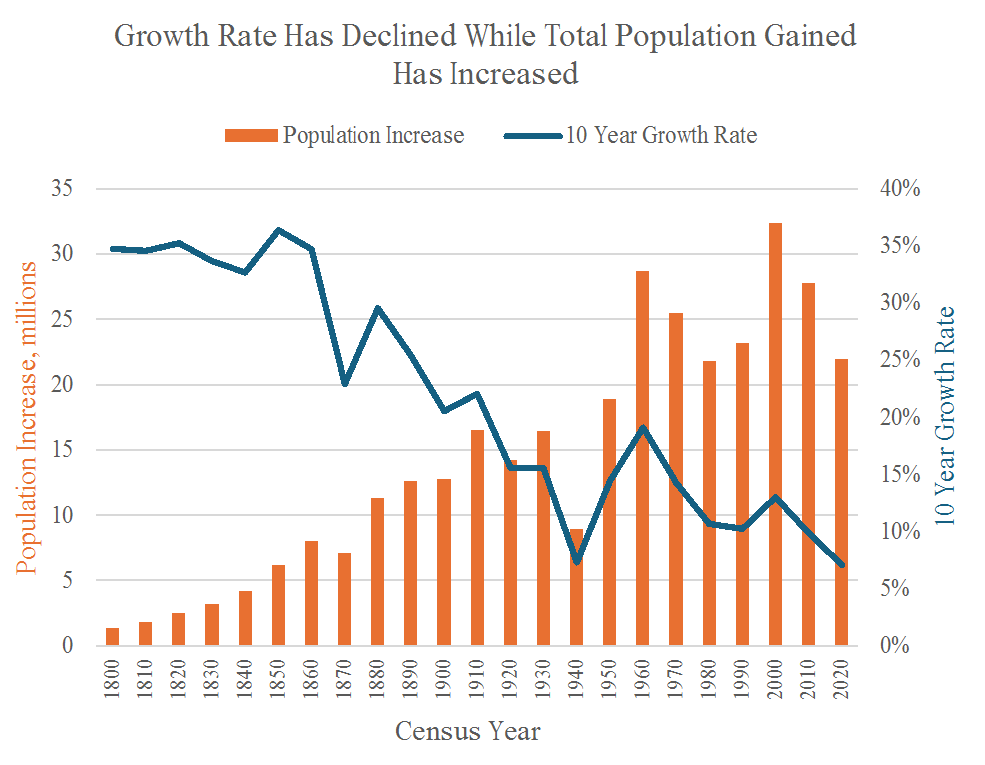

And tying Congress’s size to the cube root of the population would provide for stability going forward. Automatically adjusting the size of Congress to be the cube root of the population after each Census will remove the possibility of political manipulation of the size of Congress for partisan gain, as happened in 1920.

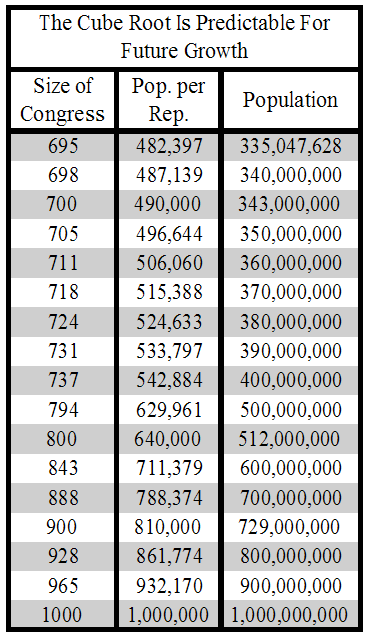

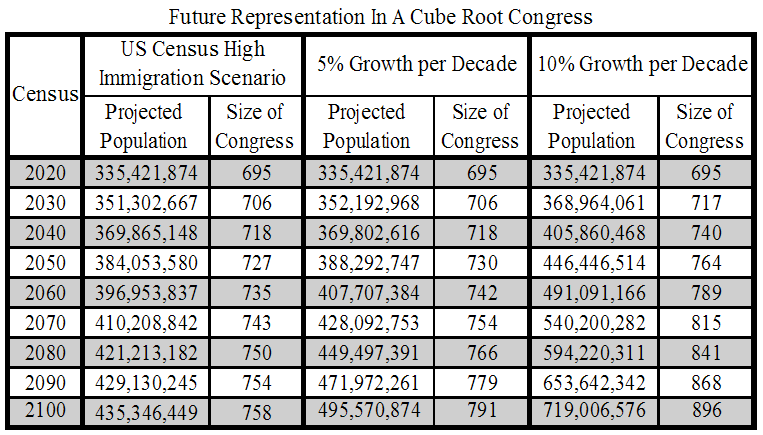

As the population of the country grows, so too would Congress. As shown in the below table, Congress would increase by just a few seats for every 10 million more Americans: from 695 representatives for 335 million Americans to 705 representatives for 350 million Americans, to 737 representatives for 400 million Americans. As the population balloons, the number of seats added slows down. If the population increased from 400 million to 500 million, Congress would increase by 57 seats. From 500 million to 600 million, Congress would increase by only 49 seats. With the cube root rule, Congress would reach 1,000 seats when the total population of the country reached 1 billion.

The number of people represented by each member of Congress would steadily increase, as well. Under a Cube Root Congress, the average number of people represented by each member would be the square of the total size of Congress. Mathematically, this results in a function in which the size of Congress is x, the number of people represented by each member of Congress is x^2, and the total population of the country is x^3.

Putting the theory into practice, how many Americans might there be in 2050 or 2100? Through immigration and longer life spans, and despite declining birth rates, our country will continue to grow. Since 1980, the population of the US has increased by about 10 percent per decade. If the United States continued to grow at 10 percent per decade, there would be 491 million Americans in 2050 and over 700 million in 2100. If Congress stayed capped at 435 members, the average member would represent over 1.6 million Americans. But by tying the size of Congress to the cube root, Congress would have 896 members to represent 719 million Americans, or one member per 802,000 Americans.

Sustained 10 percent growth per decade may be too aggressive. But even at a lower growth rate of 5 percent per decade the United States would reach a population of 496 million by 2100. The high end of the official US Census Bureau population projection would see the population reach 435 million by 2100.

However quickly or slowly our population might change, the mathematical simplicity of setting the size of Congress as the cube root of the population would allow Congress to adjust its size accordingly, and without partisan interference.

What do you think? Is the Cube Root the right way to determine how large Congress will be? If not, is there a better option? These questions may have no correct answer. I have made the case for using the Cube Root as less arbitrary, somewhat objective answer. At the very least, this would be a better way to apportion Congress than leaving it at its current, stagnant 435-members.